|

Don’t miss the Geminids as 3200 Phaethon swings

near |

|

December 10, 2017 |

|

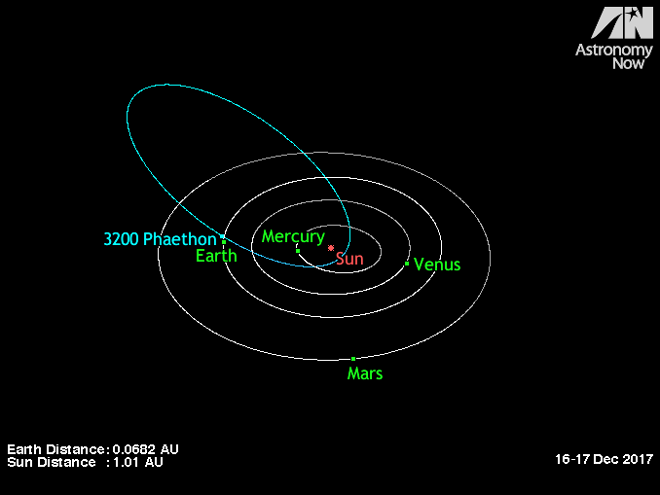

| 3200

Phaethon (blue orbit) will sweep close

to Earth on December 16, 2017, just days

after the Geminid meteor shower’s peak.

Image via Osamu Ajiki (AstroArts)/Ron

Baalke (JPL) /Ade Ashford (AN)/AstronomyNow. |

|

By Bruce McClure and Deborah Byrd

EarthSky.org

|

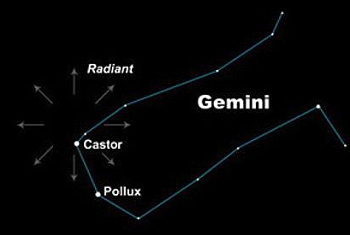

| The Geminids

seem to radiate from near the bright

star Castor in the constellation Gemini,

which lies in the east on December

evenings, highest at around 2 a.m.

|

The Geminid meteor shower – always a highlight

of the meteor year – will peak in 2017 around

the mornings of December 13 and 14. Geminid

meteors tend to be few and far between at early

evening, but intensify in number as evening

deepens into late night.

Observing around 2 a.m. is best.

This shower favors Earth’s Northern Hemisphere,

but it’s visible from the Southern Hemisphere,

too.

The Geminids’ parent body – a curious rock comet

called 3200 Phaethon – is exceedingly nearby

this year, due to make a close sweep past Earth

on December 16.

It's likely to be cloudy over the region around

North Idaho through the nights the Geminids are

most active, December 13-15, and it's going to

be cold, but there could be breaks in the

clouds, making sightings theoretically possible

at least. Those chances diminish as the Geminid

showers wane December 16, with a 70-percent

chance of snow and freezing rain in Bonners

Ferry, conditions are likely to be too overcast

and too miserable for meteor watching.

Why are these meteors called the Geminids? If

you trace the paths of the Geminid meteors

backward, they all seem to radiate from the

constellation Gemini the Twins.

This shower’s radiant point nearly coincides

with the bright star Castor in Gemini. That’s a

chance alignment, of course, as Castor lies

about 52 light-years away while these meteors

burn up in the upper atmosphere, some 60 miles

(100 km) above Earth’s surface.

Again, you don’t need to find the constellation

Gemini to watch the Geminid meteor shower. These

medium-speed meteors streak the nighttime in

many different directions and in front of

numerous age-old constellations.

|

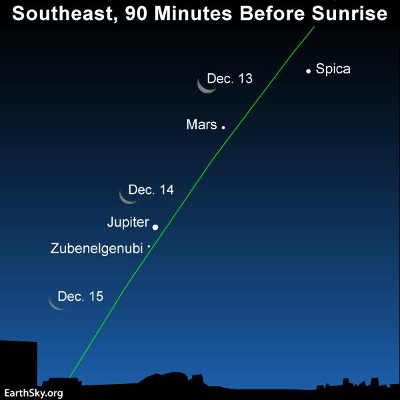

| Watch for

the waning moon, Jupiter and Mars around

the mornings of the Geminids’ peak in

2017. |

You can watch this shower in the evening – late

evening is best.

But the greatest number of meteors will fall in

the wee hours after midnight, centered around 2

a.m. local time (the time on your clock no

matter where you are on Earth), when the radiant

point is highest in the sky. As a general rule,

the higher the constellation Gemini climbs into

your sky, the more Geminid meteors you’re likely

to see.

These meteors are often bold, white and bright.

On a dark night, you can often catch 50 or more

meteors per hour.

You need no special equipment – just a dark,

open sky and maybe a sleeping bag to keep warm.

Plan to sprawl back in a hammock, lawn chair,

pile of hay or blanket on the ground. Lie down

in comfort, and look upward.

By the way, you don’t need to find a meteor

shower’s radiant point to see the shower. The

meteors will appear in all parts of the sky.

It’s even possible to have your back to the

constellation Gemini and see a Geminid meteor

fly by. However, if you trace the path of a

Geminid meteor backwards, it appears to

originate from within the constellation Gemini.

When you’re meteor-watching, it’s fun to bring

along a buddy. Then two of you can watch in

different directions. When someone sees one,

they can call out “meteor!” This technique will

let you see more meteors than one person

watching alone will see.

Be sure to give yourself at least an hour of

observing time. It takes about 20 minutes for

your eyes to adapt to the dark.

Be aware that meteors often come in spurts,

interspersed with lulls.

Every year, in December, our planet Earth

crosses the orbital path of an object called

3200 Phaethon, a mysterious body that is

sometimes referred to as a rock comet and parent

to the Geminid meteors we see on Earth.

The debris shed by 3200 Phaethon crashes into

Earth’s upper atmosphere at some 80,000 miles

(130,000 km) per hour, to vaporize as colorful

Geminid meteors.

In periods of 1.43 years, this small 5-kilometer

(3-mile) wide asteroid-type object swings

extremely close to the sun (to within one-third

of Mercury’s distance), at which juncture

intense thermal fracturing causes it to shed yet

more rubble into its orbital stream.

In 2017, 3200 Phaethon will be exceedingly

nearby around nights of the Geminid meteor

shower’s peak. This object will sweep close to

Earth – just 0.069 astronomical units (6.4

million miles, 10.3 million km, 26

lunar-distances) on December 16, 2017 at 23 UTC;

translate to your time zone.

The proximity of this object might mean a

fantastic year for the Geminids in 2017!

One of the best things about this year’s Geminid

shower is that the moon is out of the way. It’s

a waning crescent in the east before sunup and

so shouldn’t interfere much, if at all, with

your meteor-watching. Plus, the waning crescent

moon will slide past the morning planets, on the

peak mornings on the 2017 Geminid shower.

Look at the chart above. See how the moon gets

closer to the sunrise point each day? That

motion of the moon across our sky is a

translation of its motion in orbit around Earth.

Bring along your binoculars when watching for

the moon and planets, on the nights of the

Geminids’ peak. They won’t help you watch

meteors, but you’ll be able to see Jupiter in

the same binocular field of view with the star

Zubenelgenubi in the constellation Libra the

Scales. Look closely, and you’ll see that

Zubenelgenubi is a double star – two stars in

one!

You won’t see as many Geminid meteors when the

constellation Gemini sits close to the eastern

horizon during the evening hours. But the

evening hours are the best time to try to catch

an earthgrazer meteor.

An earthgrazer is a slow-moving, long-lasting

meteor that travels horizontally across the sky.

Earthgrazers are rarely seen but prove to be

especially memorable, if you should be lucky

enough to catch one. |

|

Questions or comments about this

article?

Click here to e-mail! |

|

|

|

|